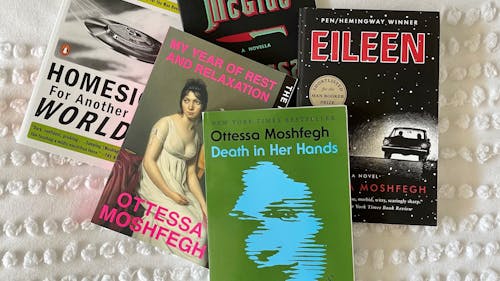

‘My Year of Rest and Relaxation': Dreary glimpse of pre-9/11 New York City with calculated characters

“My Year of Rest and Relaxation” isn’t just some novel: It’s a holy text. The 2018 book by Ottessa Moshfegh takes the reader through the jagged depths of a young, rich, thin and beautiful woman’s tumultuous mind in the early 2000s.

With the help of the questionable-at-best psychiatrist Dr. Tuttle, the unnamed narrator spends an entire year trying to stay asleep in the hopes of waking up to a new perspective. It’s a stretch for sure, but the narrator genuinely believes that she can come to terms with her life after her parents’ deaths.

“My Year of Rest and Relaxation” has been making recent rounds on highly feminine internet subcultures, like high-fashion Instagram and cherry-emoji Twitter. Influenced by the bravado of “American Psycho” and with elements of Kate Chopin’s “The Awakening,” the book successfully satirizes privileged femininity and New York City culture before the attacks of Sept. 11.

The cover of the book is “Portrait of a Young Woman in White” circa 1798 by the French painter Jacques-Louis David, and perfectly captures the bored yet affluent narrator’s attitude throughout the book.

“It was fun, but it was also really sad. I wrote it in a very sad and unsure couple of years in my life. I was moving around, and didn’t really have a home, and the book kind of became my home, a place where I belonged,” Moshfegh said about writing “My Year of Rest and Relaxation.”

The writer is known to adopt unconventional viewpoints, especially on femininity. In an article about her 17-year-old self, Moshfegh discussed the power dynamics of a relationship she had with a 65-year-old famous and seasoned writer.

“I remember thinking his waning vitality could be used to my advantage. If I succeeded in reflecting his great masculine strength, then he’d want me around, might take more of an interest in my work, tell me more, explain more, enlighten me more,” she writes.

In the same vein, throughout “My Year of Rest and Relaxation,” Moshfegh creates a character that's more complex than just the snooty, thin, judgmental person she continually proves to be. It's the narrator’s hyper-critical nature and privilege that makes her such a fascinating character.

Yes, despite yourself, the reader can’t help but root for this incredibly privileged young blonde woman who spends every minute squandering her life away. There’s this deep ugliness to the character that’s hard for the reader to look away from, combined in spurts with the character’s past trauma and perception.

How could the reader hate our narrator, who recognizes and worships Whoopi Goldberg for her undeniable authenticity?

The character Ping Xi is a brilliant example of where Moshfegh’s character-writing abilities take on a dangerously accurate ability. On the surface, Ping Xi is a gay, artsy man that uses life as a playground for his artistic whims, believing too much in a greatness of himself that doesn’t exist.

He unironically writes a quote from Mr. Misogyny himself, Pablo Picasso — “Every act of creation is an act of destruction” — on the back of the business card he sends to our narrator. He continually takes every opportunity to demean the narrator by making her his muse, completely disregarding her sense of self.

But as an Asian American man struggling to make it big in the art world, it’s hard not to sympathize, or at least, understand why he behaves the way he does throughout the text. The ways that both Ping Xi and our narrator use one another in the novel is not too far from the perhaps “politically incorrect” relationship 17-year-old Moshfegh had with the old writer.

Moshfegh also nailed the description of “the hipster,” the prelude to the artsy soft-boy aesthetic of today. Moshfegh describes them as wearing New Balance sneakers and knit caps, reading Nietzsche and David Foster Wallace, desperate to be adored for their art when “they could barely look at themselves in the mirror.” (Ouch to all the Mason Gross School of the Arts boys who may feel called out reading this).

On the other end of the spectrum of fragile masculinity exists the narrator’s on-again-off-again boyfriend Trevor, the Patrick Bateman-esque hyper-masculine archetype. By seeing Trevor, our narrator opts for what she sees as the lesser of two evils.

The narrator’s relationship with her best friend Reva, on the surface, is unbelievable. Reva is the supporting actress to our narrator’s main-character-movie-moment, and the narrator misses no chances to criticize Reva. It seems like they both hate each other’s guts. But somehow, and for very different reasons, the two of them can’t stay away from one another.

Sleep itself becomes a character throughout the text, as the narrator experiences the pushes and pulls of insomnia and longs for what she feels will cure her of the disillusionment she experiences.

As the reader falls deeper into the trenches of our narrator’s thoughts, it seems like her worldview becomes inescapable and addictive. The blasé tone of the narrator allows the reader to appreciate and understand the way that she sees the world, while also finding humor in her judgments.

Even though the book is primarily about sleep, the characters are nothing short of alive. And (damn her!) despite seeming horrible on the surface, Moshfegh’s characters are somehow entirely relatable. Her gift for chronicling the disturbing dimensions of a character’s ethos and transforming them into a person that feels alive, like someone you may know or may have known or may want to know, is Moshfegh’s greatest power as a writer.

Ultimately, the self-induced coma takes on new heights when the narrator decides to pop the fictional sleeping pill Infermiterol to sleep for three days at a time.

When she wakes up from this slumber, she’s different. “There was majesty and grace in the pace of the swaying branches of the willows. There was kindness. Pain is not the only touchstone for growth,” the narrator muses.

With this commentary on the intricate beauties of life, it appears that she’s done it! It’s hard to believe, but our narrator, an incredibly judgmental and privileged woman, has gained some weight and perspective by undertaking her sleep-induced awakening.

But this would’ve been too easy a conclusion, too much of a disservice to our narrator and the story Moshfegh attempts to write. The single page chapter that follows that full-circle reflection only reconfirms Moshfegh’s dedication to the characters she writes. Our narrator, disturbingly, yet totally on brand for her, marvels at the so-called beauty of a woman the reader is expected to believe is Reva jumping to her death out of the burning Twin Towers.

With these final words, the reader can’t help but come to a single horrifying conclusion, one far more dangerous than any amount of Infermiterol overdoses: that we are all human, living in an incredibly strange world, dealing with one another the best way that we can.