U. professor creates installation to depict experiences with active shooter drills

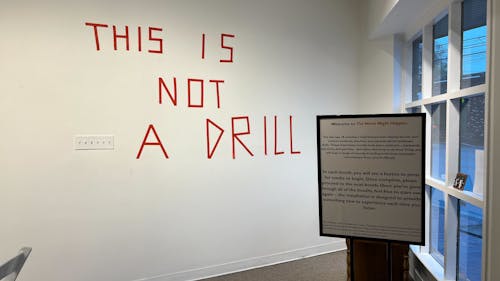

Last Sunday, the 1978 Arts Center in Maplewood debuted "This Is Not A Drill," a sensory installation featuring five booths that play recordings of students and teachers recounting their experiences with active shooter drills, according to the Maplewood Division of Arts and Culture.

Khadijah Costley White, an associate professor in the Department of Journalism and Media Studies and the creator of the installation, said active shooter drills are part of a relatively new phenomenon of amped-up security practices in American academic institutions.

She said the concept of these drills roughly started with the 1999 Columbine High School shooting and took off with the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting.

"I mean, 98 percent of American kids are going through some sort of active shooter drill right now — 98 percent. That's huge. I don't know if there's anything else in America that 98 percent of American kids are doing," she said.

Scholars have found that these drills increase depressive, anxious and suicidal thoughts among youth, White said. But they have also been shown to increase perceptions of safety on a psychological level, she said.

In her installation, White said she used booths to simulate the uncomfortable physical and emotional spaces that students and teachers enter during drills.

"So that's part of what I'm trying to do in the installation is provide that kind of disorienting effect where you're being told to do something, and you have no idea what it is and when it'll be over," she said.

Outside the booths, the installation features recordings of what White called "outside voices," or the voices of individuals who weigh in on active shooter drills despite not being as impacted by them.

"So often when we talk about school security and climate, we are listening to people who aren't actually in schools, like police officers who are in police departments or administrators … away from school buildings," White said.

Additionally, she said that the design of the booths was implemented to block visitors from the chaos and constant visual stimulation imposed by technology and modern society.

Regarding active shooter drills in practice, White said drills keep students and faculty in a constant state of heightened vigilance. Students, in particular, are not always informed whether a drill is just a drill or a true emergency, she said.

Additionally, White said that students of color and neurodivergent students and staff especially struggle with active shooter drills.

She said disabled and neurodivergent individuals are not always given the proper sensory and emotional accommodations to help them manage drills while students of color must contend with having drills being called due to often falsely being perceived as a threat.

White mentioned that one of the stories featured in the installation discussed a Latino student who brought brass knuckles to school after being bullied. This student was the subject of a code red, which is the same code that active shooter drills fall under.

"The police went from room to room holding guns out on students, looking for this particular student (who is) Latino, who they threw on the floor, arrested on the scene and dragged out and was never seen again," White said.

The concept for the installation originated when White was selected for the Whiting Foundation's Public Engagement Fellowship at the peak of the pandemic.

The fellowship is awarded annually to humanities scholars around the country and seeks to fund academic projects that address major societal issues. When White was chosen for the award, she initially intended to produce short films on the topic of school security and its impact on students and school staff, among others.

But pandemic restrictions forced White to transform her project from films to an installation. She initially launched the installation in 2021 and has since added accessibility, sensory and content accommodations, White told the Maplewood Division of Arts and Culture.

White said the key takeaway from the installation overall is the importance of evidence. She said the lack of evidence regarding the effectiveness of active shooter drills does not equate to proof that they are ineffective.

In the future, White said she hopes to move her installation to public spaces, such as libraries, rather than have it located in a space that people have to go out of their way to visit.

"I'm really proud of it. It's also terrifying ... Because I don't know if this is going to translate. Whenever you create something, put something out there, you don't know if it will touch people — if it will have any sort of impact or resonance. But I guess that's kind of what public engagement work in art and activism art is about. It's about faith to a certain extent and hoping that this one drop of a bucket will make waves," she said.