Rutgers study finds that doctors are favoring alternative acne treatments

A Rutgers study concluded that physicians are shifting away from prescribing antibiotics for treating acne, instead turning to other types of therapies and solutions, according to Rutgers Today.

Published in the journal "Dermatologic Clinics," the study was conducted by looking at previous research on short-term and long-term acne treatments from the past 10 years to see if there were any patterns.

“People are more conscious about the global health concern posed by the overuse of antibiotics and that acne is an inflammatory, not infectious, condition,” said Hilary Baldwin, clinical associate professor of dermatology at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School (RWJMS). “Overuse of antibiotics also can promote the growth of resistant bacteria, which can make treating acne more challenging.”

Those who use antibiotics for an extended period of time may see effects in their microbiome, or the trillions of microorganisms, not only on their skin, but also other areas. These changes to the microbiome have the possibility of leading to disease.

In the Rutgers report, those who used topical or oral antibiotics for acne were three times more likely than nonusers to have an increase of bacteria in the back of their throat or tonsils. If the antibiotic treatments for acne are used long enough, it was also shown to potentially increase upper respiratory infections, influence one's blood sugar level and cause more skin bacteria.

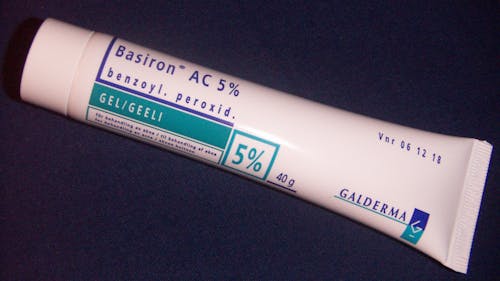

As a result, doctors are looking to a combination of alternative therapies besides antibiotics to help treat acne for the long-term. Baldwin said they were especially interested in benzoyl peroxide, an antibacterial medication that is typically used in combination with topical retinoids, which are derived from vitamin A.

Benzoyl peroxide is beneficial because it helps kill bacteria that cause acne, as well as increase skin turnover, unclog pores and prevent acne-inducing bacteria strains from being promoted.

Acne is most common among teenagers, but it is also present in adults, mainly women. Half of women in their 20s, a third in their 30s and a quarter in their 40s have acne. It was found that for women, the oral medication spironolactone was especially beneficial, though it is not Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for acne treatment.

Spironolactone is prescribed typically for those with high blood pressure, heart failure and swelling, but it also helps with disorders related to androgens, which are a type of hormone.

Hormone imbalances are one factor that can lead to acne, so doctors are now looking to more hormonal therapies to cure acne. These therapies would target androgens while acne is developing, and previous studies have shown that they are effective, safe and do not require much monitoring from the patient.

Other possible solutions are laser and light therapies, as well as regulating diet, but additional research is needed.

“Our patients often ask about the role diet plays in acne development, but that remains unclear,” Baldwin said. “However, there is some evidence that casein and whey in dairy may promote clogged pores and that low levels of omega-three polyunsaturated fatty acids in foods such as fish contribute to inflammation that can lead to acne.”

For more severe acne, the retinoid isotretinoin has been shown to be effective when used for early intervention, even without antibiotics.

“This oral medication is unique among acne therapies in that it has the potential to not just treat acne but to eradicate it. It is 80% effective if a complete course is taken,” said co-author Justin Marson, a medical student at RWJMS. “Studies also have disproven internet theories that the medication increases the risk of depression, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.”

Antibiotics are still effective for moderate to more severe cases of acne, researchers affirm. These antibiotics are also approved by the FDA, while other therapies are not.

“Numerous studies have shown that these combinations are fast, effective and help reduce the development of resistant strains of bacteria that cause acne, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that antibiotics be used for a maximum of six months,” Baldwin said.