Rutgers staff member discusses performing physics off-Broadway, building classroom demonstrations

Dave Maiullo, a physics support specialist in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, was first intrigued by physics when he was 9 years old and looked through his father’s telescope to see Saturn.

Ever since, science has played a major role in his life. Maiullo, who recently won a Staff Excellence Award from the School of Arts and Sciences, said he excelled in science courses in high school and later received a bachelor’s degree in physics from Rutgers.

He realized, though, that he did not necessarily want to become a physics professor, so the year after he graduated, Maiullo worked on a project to build a particle detector in Japan. After the installation process was finished, he returned to Rutgers and took on the job of building demonstrations for the physics department.

“When I took physics here at Rutgers, I didn’t see a single demonstration … but they said they wanted me to make it grow,” he said.

Mauillo soon realized that building the demonstrations was fun and kept him young, since he was essentially “playing” with toys that connected to physics. As part of his job, he figures out what professors are trying to show, and then builds a specific demonstration to convey the concept. Currently, the physics department has more than 3,500 demonstrations in total.

Demonstrations were important in the classroom because they made physics real, Mauillo said. Much of what students did in classrooms were esoteric, meaning they saw equations and only worked on trying to get the numbers right.

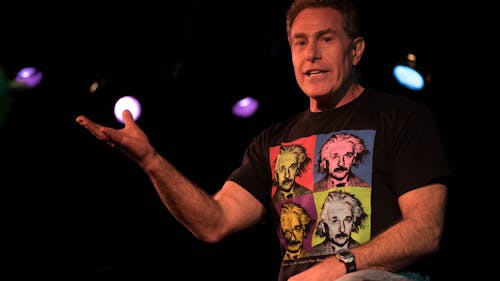

After spending time building demonstrations at Rutgers, Mauillo then started to develop public shows. He first started with schools, libraries and senior centers, then eventually performed off-Broadway in “That Physics Show.”

“(People) took (physics) in high school and probably failed it,” he said. “So when you go to a physics show and you realize how exciting it is, how it’s really not scary and is what’s around you all the time … that’s what I was trying to achieve.”

At first, Mauillo was hesitant to take a position performing off-Broadway because of the time commitment, especially since he had children. After being encouraged by Eric Krebs, who founded the George Street Playhouse, he said he would give “That Physics Show” a shot.

Since first running four years ago, approximately 540 shows have been performed and more than 60,000 people have watched it. Mauillo said in the show, he would start by introducing basic physics concepts and building on them throughout the show’s 1.5-hourlong duration.

First, he would explain how objects move, then relating that to circulation motion, then to the concept of moment of inertia. The show then transitions to waves, specifically in the context of sound waves and light waves, and eventually concludes with an actor lying on a bed of nails as the finale.

The show has even become international. After being performed in New York City, it was soon developed in China, where it won the award for Best Children’s Show in Shanghai. Mauillo said there were even people in Brazil who were hoping to incorporate the show into the country.

“It works universally, because the physics is universal,” he said.

The work he was doing was especially significant because it bridges the gap between science and art. Mauillo said an issue today was that communication was lacking, meaning that artists tended to avoid science and scientists did the same with art.

Though it is a challenge to make physics an art form, Mauillo said a trick was to use equipment and devices that anyone could understand. For instance, to demonstrate advanced concepts in sinking and floating, he would demonstrate everything using water and soda cans.

“If you can do that to 60,000 people of all different types, nationalities and age groups … that’s going to help,” he said. “I think that the more people understand the science of life, the better the society.”

Some of the hopes he has for the show is that it inspires children to become interested in science, motivates more women to take science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) courses and convinces people that physics is not as bad as they believe it to be.

His favorite part of his job, though, is two-fold.

“One is working with all of (the students). I get a lot of ideas from their energy, and a lot of inspiration. It keeps me young to work with them,” he said. “The second part is watching someone, whether it’s a young person or grandmother in my show, all of a sudden go, ‘Oh, I got it!’”