TECH: What exactly happened with the Internet blackout last week?

Internet users were unable to access some of the world’s busiest websites, including Twitter, reddit, Github, Spotify, the New York Times, several Amazon Web Services clients and many others last Friday after a massive Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack that interrupted service to Dyn Inc., a managed DNS service provider.

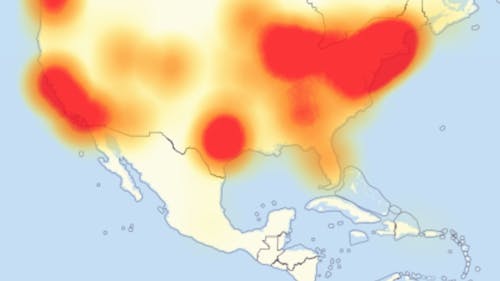

Dyn was attacked three times on Friday— twice in the morning and again in the early afternoon. While the first two had a massive impact on the East coast (and other parts of the world), the third did not impact users as much.

Before I explain what exactly all that means, we need to understand the terminology that will be used.

Domain Name System

Domain Name Systems (DNS) are protocols that act as a map for computers trying to find websites. When people might type in a URL like www.dailytargum.com, their computer needs to find the website’s IP address. DNS servers provide that address.

In other words, a Rutgers student might know they have to go to the Busch Student Center. While that is its name, in order to actually find it they will need to know its address is 604 Bartholomew Rd in Piscataway, New Jersey. The DNS provider is what translates “Busch Student Center” to “604 Bartholomew” online.

Distributed Denial of Service

A Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack is a specific type of cyberattack that disrupts service to their targets by essentially overloading them with information. Under normal use, a server might send a request for communication to another, which the receiver would respond to.

Under a DDoS, the receiver is hit by millions upon millions of requests, which overwhelms it, preventing it from responding to normal requests. Rutgers has been impacted by several DDoS attacks over the last two years.

Internet of Things

The Internet of Things refers to networked everyday objects that people might have in their homes or cars. Any “smart” device might count, ranging from toasters and fridges to nanny cams and DVR devices.

Every object in the IoT has to be able to connect to the internet to transmit data, and an increasingly large number of objects have this ability.

Botnet

Dyn was taken down through the use of the Mirai botnet. Botnets are a series of hijacked devices which are used to disrupt service through a DDoS.

Malicious software called a bot is used to slave the victimized machine to do its own bidding. Hundreds of thousands computers might be taken over in this manner, and while only personal computers used to be part of botnets, thanks to the IoT, other devices can now be used.

The Mirai botnet is a specific group of hijacked devices, using an open-source piece of malware named Mirai. This code was released to the general Internet earlier in October, but was used in the past against specific websites.

So how’s all this stuff connected?

For the sake of simplicity, we will say that there are three components needed to pull up a webpage in your web browser. The web browser is the sender — when you type a URL in, it requests a page. The receiver is the server that has the page.

In order for the sender to talk to the receiver, it must ask the DNS provider for directions. The DNS provider is effectively a middleman for digital requests.

When Rutgers was hit by DDoS attacks over the last few years, students were unable to access University systems because the receivers — University systems — were flooded with requests.

On Friday morning, when a large chunk of the internet went out, it was because Dyn, the middleman in the above scenario, was rendered nonfunctional by a massive DDoS. The receivers were still operational, but the senders could not find them.

This outage impacted users not only on the Eastern seaboard, but in several other nations, including the United Kingdom, France and Germany, among other European nations.

This wasn’t the largest DDoS attack ever seen, but it was pretty big. The largest recent DDoS attacks all share a commonality though: they all depended on commandeered Internet of Things devices.

Hacktivist group New World Hackers claimed responsibility for the attack on Sunday, though their involvement has not been confirmed by any law enforcement agency yet.

New World Hackers also formally “retired” on Sunday through a Twitter announcement.

Okay, the internet had issues. So what?

Friday saw one of the largest disruptions due to a DDoS attack to date, and because it was carried out through open-source malware, which hijacked devices from the IoT, it can happen again.

As stated above, the Internet of Things refers to everyday devices that are connected to the internet, which are not necessarily traditional personal computers.

The Mirai botnet was composed of DVR devices, routers and webcams, among other machines. Unlike traditional personal computers, these tools may not have any sort of security beyond a factory password.

As a result, it is relatively easy to break into them. At least one manufacturer is already recalling webcams with poor security features as a result of the attack.

Around 500,000 devices might be infected by the Mirai malware, according to Level 3 Communications. Level 3 is one of the security firms Rutgers hired to help mitigate DDoS attacks* last year.

There might be as many as 15 billion devices connected to the internet that are part of the IoT, while only a few might have cybersecurity features installed.

This state of affairs might require government intervention to change.

Why wasn’t I impacted?

Several websites migrated to different, unaffected DNS providers, which allowed users to access websites like Twitter as normal. Because of this, users were able to access those websites.

Providers like OpenDNS aided users in avoiding the internet blackout by providing a new “middleman” to help them find the websites they were looking for.

Dyn was able to resolve a large number of their services as well, restoring internet access to most users within a few hours.

Why does this matter?

Dyn Chief Strategy Officer Kyle York said the number, type, duration, scale and complexity of cyberattacks are all increasing.

Internet firm Akamai reported that in the second quarter of 2016 alone, DDoS attacks had increased by 129 percent compared to the second quarter of 2015.

DDoS attacks cost victim companies money. The more powerful the attack, the greater the cost could be. On average, every minute of downtime costs the victim company roughly $22,000. These costs come from companies being unable to operate online.

In some instances, intraoffice work comes to a standstill. When Rutgers suffered from DDoS attacks, students, staff and faculty alike could not access University servers or systems, preventing them from completing tasks.

Companies also lose money when customers or clients are unable to access their websites.

Some companies can lost even more to an attack — cybersecurity firm Incapsula estimated that companies might lose half a million dollars from a single attack, though they estimated an average of $40,000 lost per hour of downtime.

Beyond the immediate financial costs, Incapsula said DDoS attacks might result in customers losing trust or virus infection, both of which may negatively impact the company.

Some attacks might be damaging enough to require hardware replacement, which further costs the company money.

*Editor’s note: The NJ Advance Media article refers to the DDoS attacks on Rutgers as a “hack,” but the two are different types of cyberattacks.

Nikhilesh De is the news editor of The Daily Targum. He is a School of Engineering senior. Follow him on Twitter @nikhileshde for more.