Researcher explains effects of brain injuries

Nearly 140 people in the United States die from a traumatic brain injury (TBI) every day, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

A TBI is some bump, blow or jolt to the head that disrupts the brain’s function, according to the CDC.

Such a serious medical condition is of interest to those in the neuroscience field, said Bonnie Firestein, a professor in the Department of Cell Biology and Neuroscience, who has done previous research concerning the central nervous system as well as injuries affecting the brain.

“(A) traumatic brain injury can occur in response to a mechanical injury or damage to the brain and brain tissue,” she said. “Processes such as the tearing of axons and dendrites from neurons as well as excess glutamate release occur. This will act to harm neurons, and sometimes it will cause cell death.”

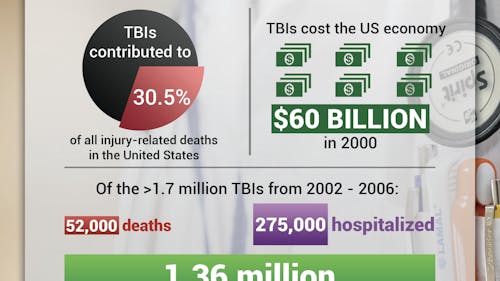

According to the CDC, these injuries effect 1.7 million people per year, of whom 52,000 die annually. Another 275,000 are hospitalized, but the remaining 80 percent of victims are treated and released.

These injuries cost the U.S. economy $60 billion in 2001, and made up 30.5 percent of injury-related deaths in the nation.

Glutamate essentially excites the nerve cells it comes in contact with. An excess of glutamate, can overexcite the nerve cells to the point where it leads to cell damage and even cell death, according to Huntington’s Outreach Project for Education at Stanford (HOPES).

The severity of a TBI can also play a role in mental and physical capabilities, Firestein said.

Consequences include neurocognitive effects and disturbances to personality, but she said the main complaint is memory loss.

Despite these noticeable differences, one cannot truly understand what a person with a TBI is actually going through, said Katerina Liu, a School of Arts and Sciences first-year student.

“(TBI) takes a toll on them physically, mentally and emotionally,” she said. “Taking a hit to the head is a big setback in a lot of ways because the brain before really controlled your entire body, but now you have a limitation as to what you can and can’t do.”

Traumatic brain injuries can place a negative impact on college students as well, impairing a person's focus and retention of information, Firestein said.

Receiving a blow to the head is not something college students are too concerned about, yet the consequences could potentially be life-changing, Liu said.

“It can put a strain on a lot of relationships. The person who they knew before might be someone else internally,” she said. “I know that if this were to happen to someone that I knew I would really try to reach out and be a good friend.”

Certain groups are more prone than others to receiving a blow to the head and are advised to be cautious when performing tasks that could increase the likelihood of receiving a traumatic brain injury, Firestein said.

“College students should be fully aware that if they’re engaging in a sport that’s dangerous, they should really keep an eye out for signs that might signify that they’ve had a concussion,” she said.

TBIs are classified as mild, moderate or severe, and further classified as subsets of those levels of severity, she said.

One type of brain injury is a concussion and is classified as a mild traumatic brain injury depending on how mild it is, she said.

These injuries can have both short-term and long-term effects, but protecting against concussions is not necessarily the first priority of college athletes, she said.

Rashmi Pradhan, a School of Arts and Sciences first-year student, believes athletes should practice proper safety.

“When they’re running on the field, they’re not thinking about how they could protect themselves. They’re thinking about getting the ball and running," she said. "So it’s really important that they practice good safety and they have helmets that could absorb the shock of an impact."

There has been an increase in the number of people experiencing traumatic brain injuries due to engagement in military combat, Firestein said.

If someone receives a blow to the head, doctors have methods for treating such injuries. This requires more of a microscopic and biological understanding of what is happening in the brain, she said.

When treating a traumatic brain injury, it is important for doctors and any medical professional to treat what are called secondary injuries, or the lingering effects of the primary injury, as those can cause further damage to neurons, she said.

Merely looking at a patient in order to diagnose a traumatic brain injury is not sufficient. At times, she said it requires additional in-depth testing for an accurate diagnosis.

The quantity of a particular molecule, or biomarker, changes when a person has a disorder, disease or injury. Measuring it in comparison to a normal level could reveal the presence of a TBI.

"When you’re looking for a biomarker for traumatic brain injury, maybe you won’t see the symptoms right away," she said. "But if you take blood and you look for a particular molecule, the quantity might have increased or decreased as opposed to a normal person’s biomarker."

Although there has been a considerable amount of research completed on traumatic brain injury, researchers have only begun to scratch the surface of learning about the inner depths of the brain.

“What’s really fascinating is the fact that suddenly after years of issues, some patients will recover, and we really don’t understand what it is about the brain that would allow it to recover,” Firestein said. “I think there are so many unanswered questions and so much research is needed in (neuroscience).”

Akhil Gumidyala is a School of Environmental and Biological Sciences first-year student. He is a contributing writer for The Daily Targum.